If we ask ourselves the question that William Shakespeare penned hundreds of years ago — “So what’s in a name?” that which we call a rose. By any other name would smell as sweet…” — then we are to believe that a name doesn’t really mean a lot. What is important is what something is, not what it is called. If that’s the case, why then do we spend so much time nowadays trying to figure out the perfect name for our children?

The hype for creative names is a fairly recent trend. Leading up to the 20th Century, our American ancestors (comprising a multitude of cultures) followed a fairly simple format. Oldest sons were given their paternal grandfather’s name, the next oldest son was given his father’s name, and later sons were named for their father’s brothers. This worked fine in families with a lot of children, which was usually the case back in the day. While the format was simple for our ancestors, it gives genealogists headaches because they have to spend a lot more time and energy wading through identical names over many generations – a process that is confusing and time consuming.

The 1900s ushered in innovation, and with it, innovative names. The competition among favorite first names is like watching racehorses jockey for position. From 1880 to 1930 John and Mary won across the board for favorite names. Not until 1930 did Robert nose ahead of John, while Mary continued as the favorite girl’s name for two more decades. Mary was edged out by Linda, who became the front runner in the 1950s.

It was in the mid-20th Century, however, when creative baby names really hit the home stretch. The popularity of some of these names has followed such viral trends as to signal a person’s birth date within a year or two.

Just for grins, I have included favorite baby names according to decade, starting with the 1880s. This list was culled courtesy of BabyCenter.com.

1880: John and Mary

1890: John and Mary

1900: John and Mary

1910: John and Mary

1920: John and Mary

1930: Robert and Mary

1940: James and Mary

1950: James and Linda

1960: David and Mary

1970: Michael and Jennifer

1980: Michael and Jennifer

1990: Michael and Jessica

2000: Michael and Hannah

2010: Aiden and Sophia

Aiden and Sophia continued to hold their first place position in 2011. What the top names for 2012 will be is anyone’s guess. What are your Win Bet names for this year?

As enthralled as parents are today to find the perfect name for their child, you would not have found parents back in the Middle Ages thumbing through parchment manuscripts looking for a trendy name for little Junior born in 1225. Likewise, these sorts of lists would not have been as interesting then as they are now. For the most part, our distant ancestors chose names for their children based on cultural or regional rules. The Spanish gave their children two names (separated by “y” meaning “and”), one from each parent. The French and Italian added a “de” or “di” (meaning “of” or “from”), respectively, in between the first and last name to explain the child’s family or town connection. The Scottish and Irish used Mac and Mc to indicate “son of;” while the Polish used icz, -wicz, and –ycz to do the same thing.

What a difference a thousand years makes. Parents today read magazines, lists, and polls of popular names; they watch Entertainment Tonight to see what celebrities are naming their children, and additionally study the derivation and meaning of each name so that their progeny will begin life with a positive label. So in the end, it’s the parents’ responsibility to choose either a worthy and suitable name for their offspring, or some obnoxious moniker (that seemed “cool” at the time) that will saddle the child with a lifetime of teasing. That means it is important not to fall under the spell of some celebrities who have chosen “special” names for their children. For example: Sylvester Stallone named his child Sage Moonblood; Michael Jackson’s younger son is Blanket, while Michael’s brother Jermaine named his child Jermajesty; Penn Jilette chose Moxie Crimefighter; and Shannyn Sossamon named her child Audio Silence. The winner of all time, however, is Frank Zappa who named his children: Moon Unit, Dweezil, and Diva Thin Muffin.

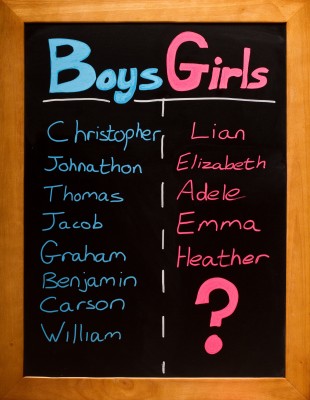

So where does this leave expectant parents on this 236th anniversary of the Signing of the Declaration of Independence? Well, upcoming parents are actually in a perfect position to name their child (boy or girl) after a Revolutionary War Patriot, thus proving that they and their offspring are Rebels, Revolutionaries, and True Americans. This is a perfect chance for American parents to move away from Jacob, Mason, Heather, and Tiffany, and select fresh new Revolutionary names.

Trust me, there were plenty of Patriots with regular names, such as Robert, Edward, Peter, and John, but for the sake of rebellion and trendiness, I will list a few boys’ names that are unique by today’s standards and also happen to be the first names of Revolutionary War Patriots. How do these strike you: Jeremiah, Sterling, Burwell, Zalmon, Hezekiah, Goin, Zadok, Philemon, and my all-time favorite – Narcissus. Frankly, Narcissus is a perfect name for a lot of men today; it is of Greek derivation and means egoism, vanity, conceit, self-love, and self-absorption.

Most of Colonial girls’ names, such as Abigail, Grace, Deborah, and Anna, paled in comparison to other popular names, such as Comfort, Temperance, Remember, Thankful, Mercy, Modesty, Patience, and Verity. Names like Hepzubah and Electa would do well for female rock stars today. Don’t think for a second that Colonial females with names evoking the fairer sex did not aid in the fight for American Independence; there were a number of Patriots in petticoats who fought valiantly or used their smarts to achieve Freedom for the colonies.

Nanyehi was the daughter of a Cherokee mother and a white father. Known to non-Native Americans as Nancy Ward, Nanyehi was called “Beloved Woman” by the Cherokee Nation; she served as the head of the Women’s Council and a member of the Council of Chiefs. While the Cherokee were split between the two sides during the American Revolution, Nancy took up the cause for American settlers and soldiers, providing them with advanced warning of enemy attacks.

Sybil Luddington, also known as the “Female Paul Revere,” rode about 40 miles through New York Counties Putnam and Duchess to warn the militia that British troops were burning Danbury, Connecticut (a Patriot supply center). Luddington’s name is spelled a number of ways: her tombstone is etched with “Sibbell,” the 1810 census lists her as “Sibel,” and her sister spelled her name “Sebil.” The Patriot preferred “Sebal,” and even signed her Revolutionary War pension application with that spelling.

Mercy Otis Warren is credited with writing the first history of the Revolutionary War, using the notes she took during the meetings of the Committee of Correspondence, which was convened in her house. Her book was titled History of the Rise, Progress, and Termination of the American Revolution and published in 1805. Mercy also wrote six plays – one of which was titled The Blockheads – all of which made fun of the British, which was a punishable offense.

Prudence Wright rallied the women of Groton, Massachusetts, to don men’s clothing and arm themselves with weapons, including pitchforks, to defend the bridge leading into town. The women hid and watched to see where the British hid their secret messages. Once the enemy had passed, the women intercepted the messages and passed them on to the local Patriot Committee of Safety.

American-born Patience Wright, who was best known for her molded wax sculptures, was also a painter and poetess. Reported to be a Quaker and a vegetarian, Patience was also known for her salty language. She moved to England in 1772 to pursue her artwork as an occupation, sculpting King George III, as well as other members of British royalty and nobility. When the American Revolution commenced in 1776, Patience made the decision to remain in England, where she busied herself as a spy for the Patriot cause – she collected information from her patrons, which she secreted inside her wax figures bound for her sister’s waxworks in nascent America.

It just may be that either you or someone you know is expecting a baby. Whether it is a friend or a family member, it matters not, because when it comes to naming a baby, we all have our two cents to put in on what it should be. This 4th of July, think in a Revolutionary way. We need a little more Comfort, Mercy, Modesty, Patience, and Verity in this world of ours . . . don’t you agree?

For help with your ancestry research, speak to a professional genealogist today.